- Harvard Business School – Jeremy C. Stein and Adi Sunderam: Gradualism in Monetary Policy: A Time-Consistency Problem?

We develop a model of monetary policy with two key features: (i) the central bank has private information about its long-run target for the policy rate; and (ii) the central bank is averse to bond-market volatility. In this setting, discretionary monetary policy is gradualist, or inertial, in the sense that the central bank only adjusts the policy rate slowly in response to changes in its privately-observed target. Such gradualism reflects an attempt to not spook the bond market. However, this effort ends up being thwarted in equilibrium, as long-term rates rationally react more to a given move in short rates when the central bank moves more gradually. The same desire to mitigate bond-market volatility can lead the central bank to lower short rates sharply when publicly-observed term premiums rise. In both cases, there is a time-consistency problem, and society would be better off appointing a central banker who cares less about the bond market. We also discuss the implications of our model for forward guidance once the economy is away from the zero lower bound. - The Washington Post – Robert J. Samuelson: The weakened Fed

These are worrying days for the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank. Surrounded by critics on the left and right, it can hardly do anything without being second-guessed or denounced. Last week, the Fed decided not to raise its target “fed funds” rate, a move that was praised by some economists but was greeted by steep drops in stock prices. This captures the Fed’s precarious position: supported by some, scorned by others. Over the past decade, there has been a profound shift in its public standing. Before the 2008-09 financial crisis, the Fed enjoyed enormous prestige and freedom of action. All the Fed had to do, it seemed, was tweak short-term interest rates to keep expansions long and recessions short. What’s clear now is that we vastly exaggerated the Fed’s powers of economic management. Since 2008, the Fed has not only kept short-term interest rates near zero but has also poured nearly $4 trillion into the economy by buying U.S. Treasury securities and mortgage bonds (so-called “quantitative easing,” or QE). These policies almost certainly helped the economy, but the extent of the help is unclear and subject to legitimate disagreement. Regardless, the recovery has been frustratingly slow. The Fed’s reputation has suffered. Increasingly forgotten is its success during 2008 and 2009 in preventing another Great Depression by acting as “lender of last resort” for the financial system. Instead, Fed policies are misleadingly identified as part of the problem and in need of overhaul. The Fed is increasingly friendless. The sluggish recovery has turned it into a scapegoat. What we should have learned is that its powers, though considerable, are limited. Years of ultra-easy credit have not triggered the faster growth that most Americans desire. Even with the economy near “full employment” (August’s unemployment rate: 5.1 percent), living standards are barely budging.

Comment

<Click on chart for larger image>

Stein and Sunderam’s conclusions are similar to comments we made earlier this month on why even one rate hike matters.

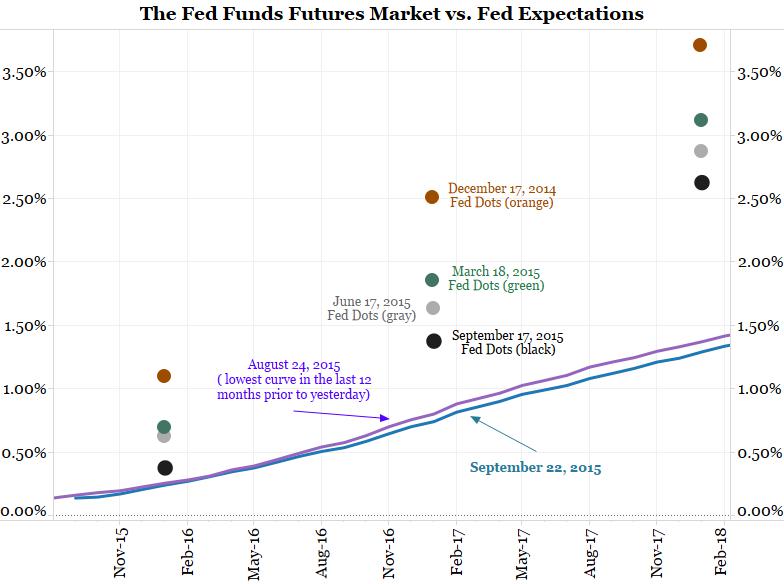

As the chart below shows, the fed fund futures forward curve (blue line) is at a new 12-month low (the purple line shows the previous 12-month low) and is well below the Fed’s expectations. If the Fed would have hiked last week, the markets would be forced to take Yellen’s words much more seriously. As a result, the forward curve would have likely moved much closer to the Fed’s latest projections. In other words the line would have to go through the black dots. Such an adjustment, moving higher by 100 bps, would have been a big change for the bond market.

This chart shows the market and the Fed are almost in different worlds when it comes to fed funds expectations. According to Stein and Sunderam, no amount of forward guidance or promises of “one hike and pause” can reconcile this. Only an actual hike will force the fed funds market to become more closely aligned with Fed projections.