- Bloomberg.com – There’s Never Been a President This Unpopular With an Economy This Good

‘Circus in Washington’ seen drowning out good economic news

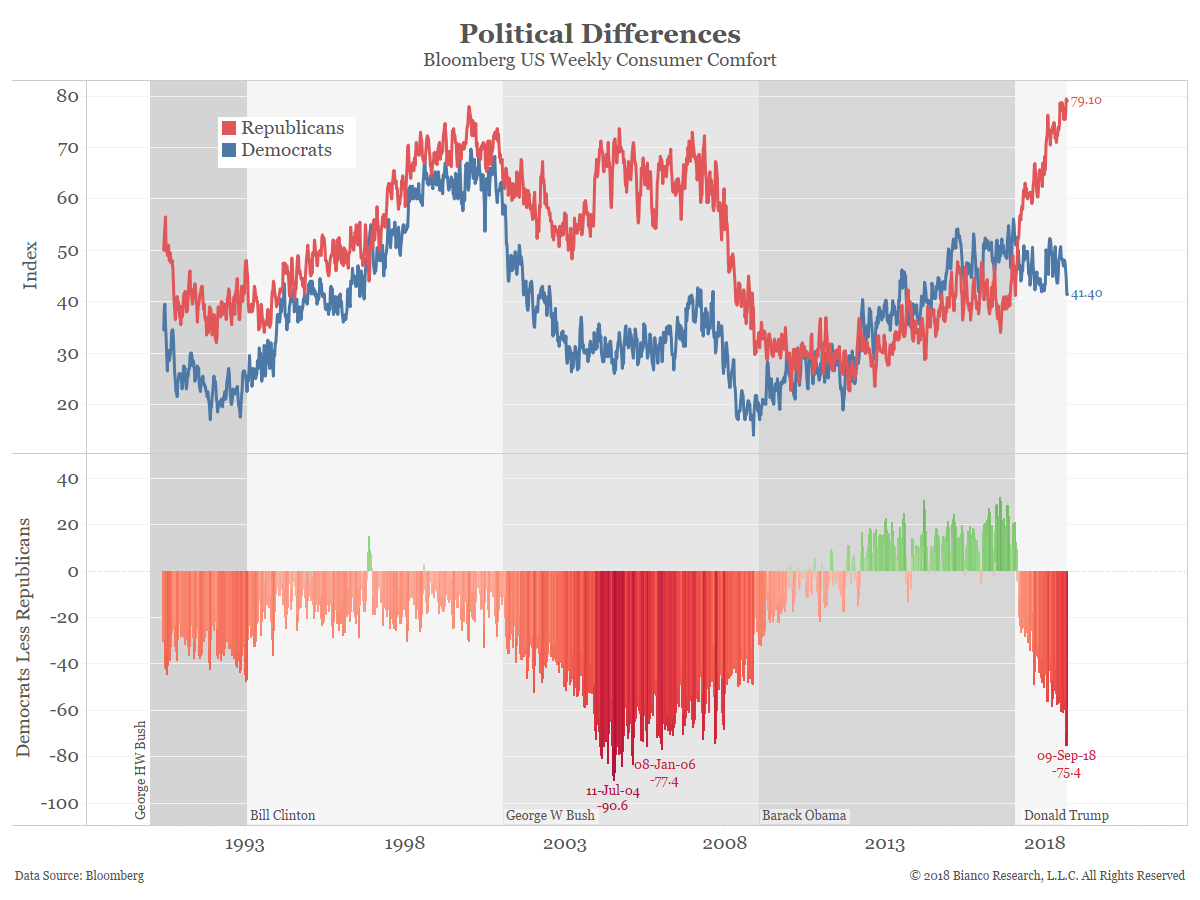

Trump’s unpopularity poses problems for Republican candidatesPresident Donald Trump’s unpopularity is unprecedented given the strength of the economy. That’s according to a Bloomberg analysis of polling data. It shows that Trump is the first U.S. leader dating back to at least Ronald Reagan whose approval rating is consistently low and lagging consumers’ favorable assessment of the economy. … The result of all the ramped-up rhetoric in the nation’s capital: Republicans and Democrats are as divided as they’ve been for 14 years when it comes to their overall assessment of how they’re doing. A polarization index, which measures the difference in sentiment between supporters of the two parties in the Consumer Comfort poll, shows the gap widening rapidly since Trump took office in January 2017. It’s now approaching levels last seen in 2004 during the height of the war in Iraq.

- Psychology Today – Why Has America Become So Divided?

Four reasons the United States doesn’t seem so united anymore.In a more recent study published just this year entitled “Ideologues Without Issues: The Polarizing Consequences of Ideological Identities,” University of Maryland professor Lilliana Mason extended Iyengar’s findings by distinguishing between two separate aspects of political ideology — “issue-based” (defined by what one believes about the issues) and “identity-based” (defined by one’s social identity of party affiliation).3 In Dr. Mason’s examination of political survey data, by far the more potent predictor of social distance was identity-based ideology — how we identify ourselves as Democrats or liberals as opposed to Republicans or conservatives — not where we stand on the issues. Collectively, these results indicate that it’s the social identifying role of ideological affiliation that’s paramount in guiding our negative emotional responses to those on the other side of the political fence. This conclusion helps us to understand a few seemingly puzzling aspects of politics today — for example, how politicians can “pivot” on the issues when running for office and how key components of traditional party platforms can sometimes turn on a dime (e.g. the GOP and Russia), and why hypocrisy seems to run rampant in politics today. For much of the voting public, political affiliation isn’t so much about the issues as it is about being part of “Team Red” and “Team Blue.” So opposed between “us” and “them,” “liberals become “libtards,” “conservatives” become “fascists,” and the possibility of finding common ground flies out the window. As NYU philosophy professor Kwame Anthony Appiah recently put it, “all politics is identity politics.”

Summary

Comment

The stories above highlight the level of political polarization among the public. This can be seen in the chart above, which breaks down consumer comfort by political affiliation. Republicans (red) are currently much more comfortable than Democrats (blue). In fact, the bars in the bottom panel show the spread between these two groups’ opinions is its widest in 12 years and approaching the record seen in 2004, at the height of the Iraq War.

Polarized Congress

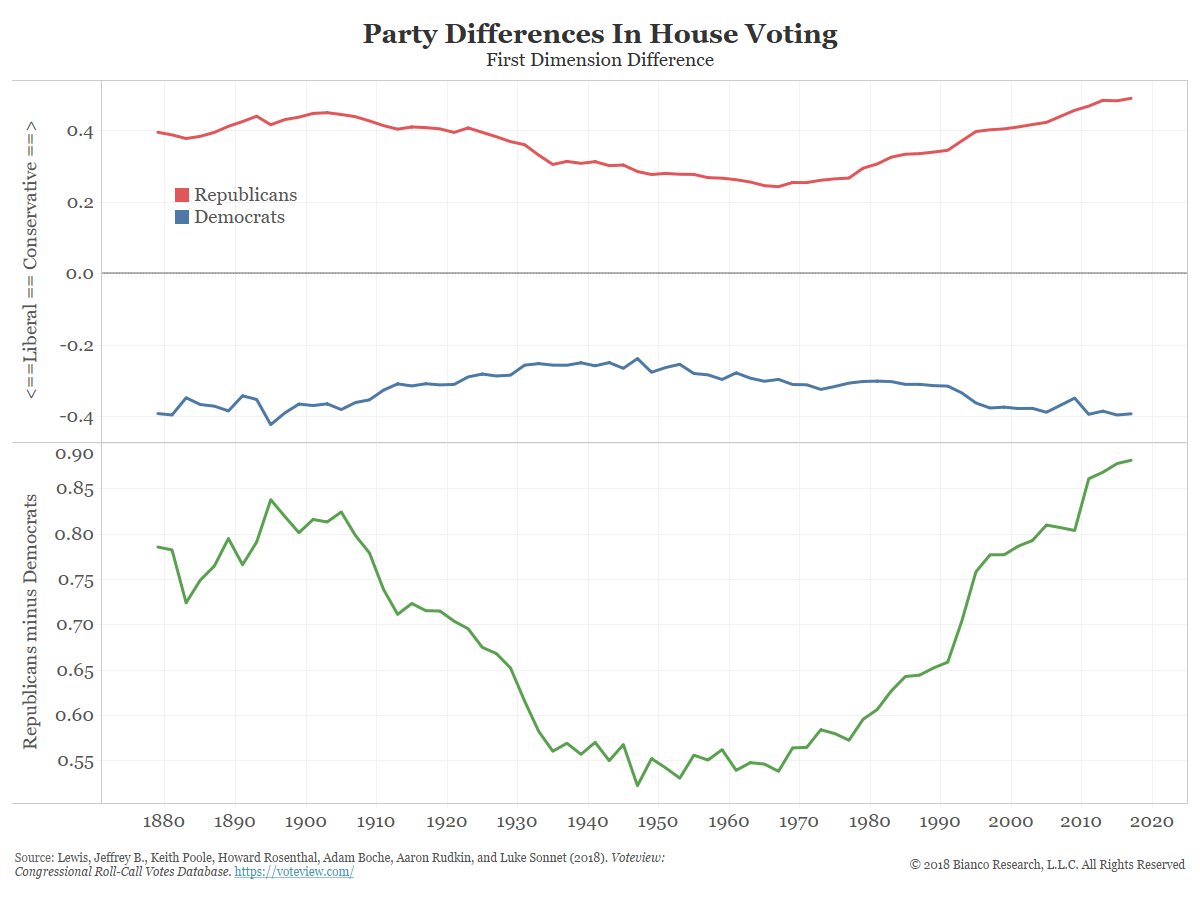

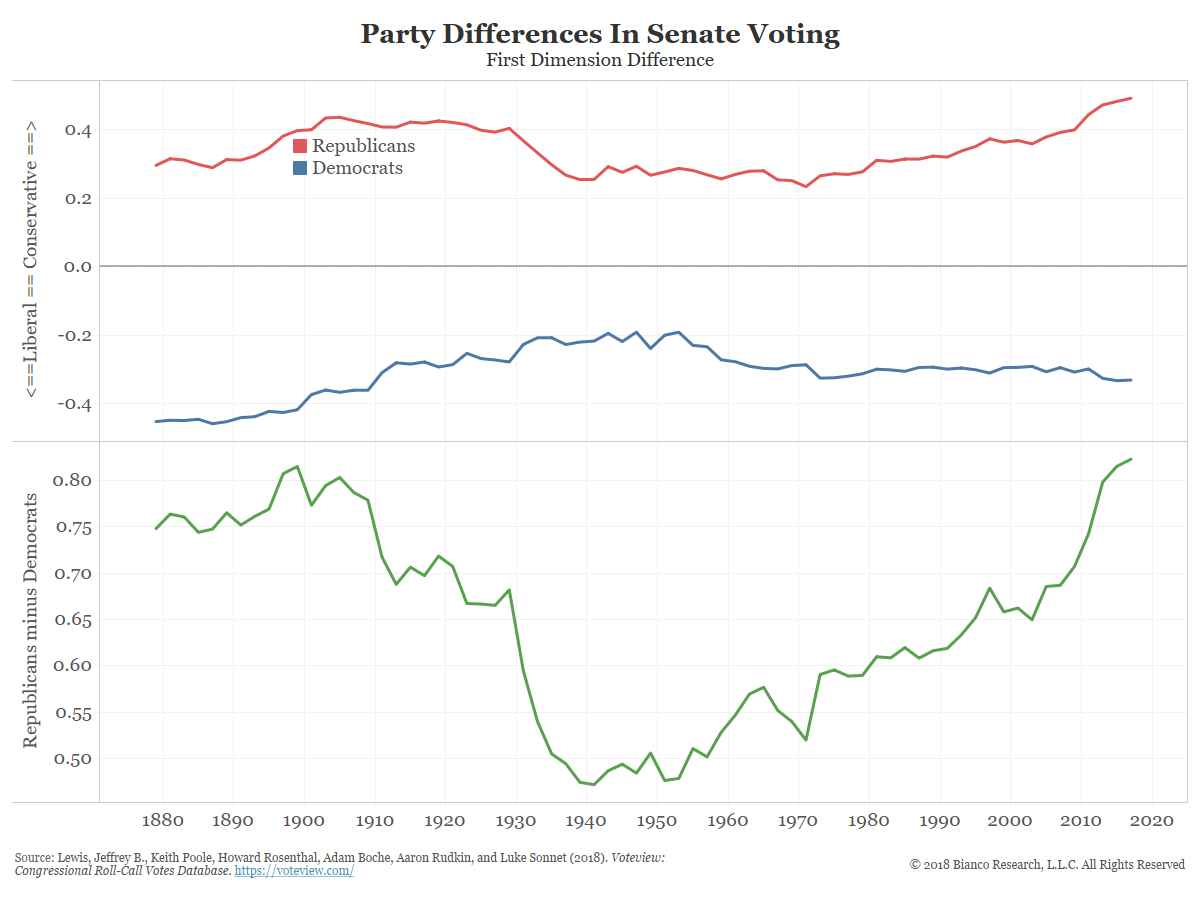

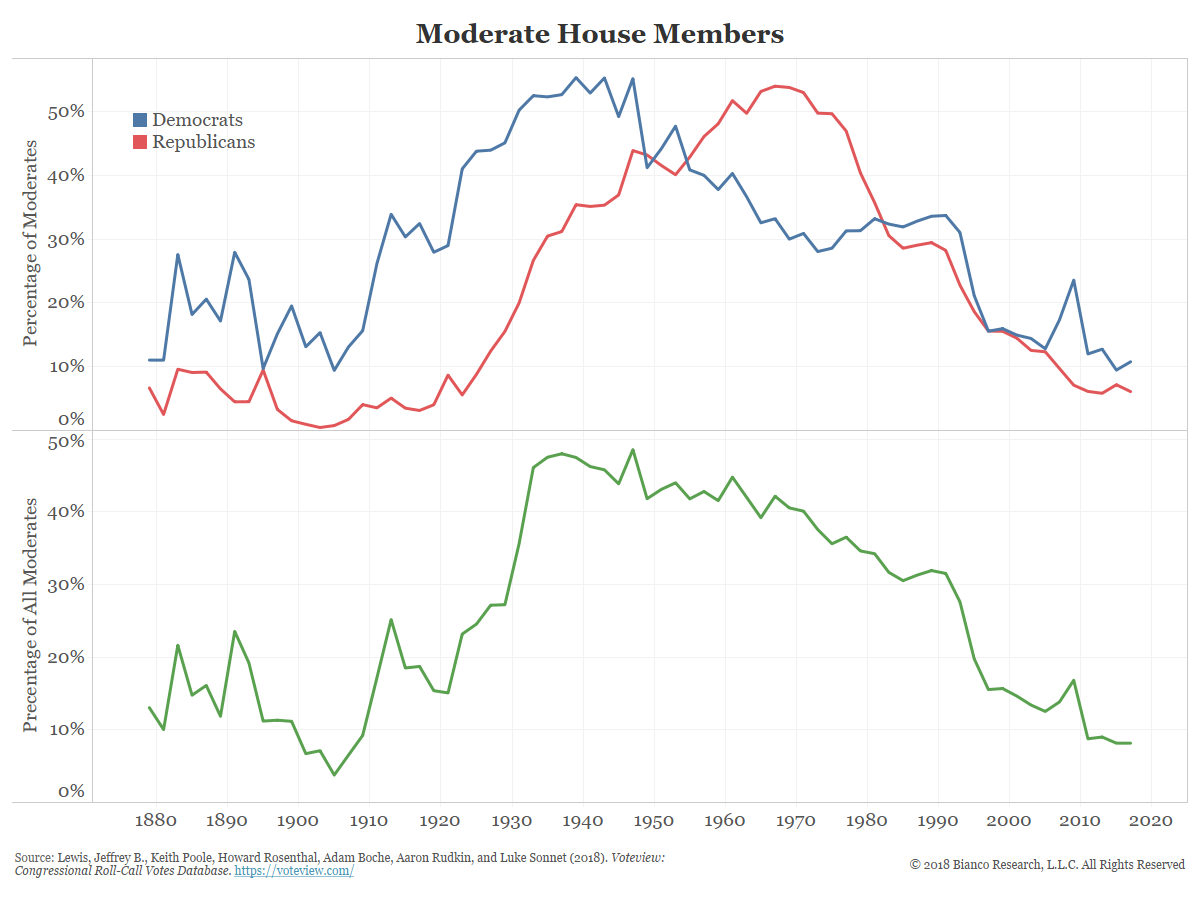

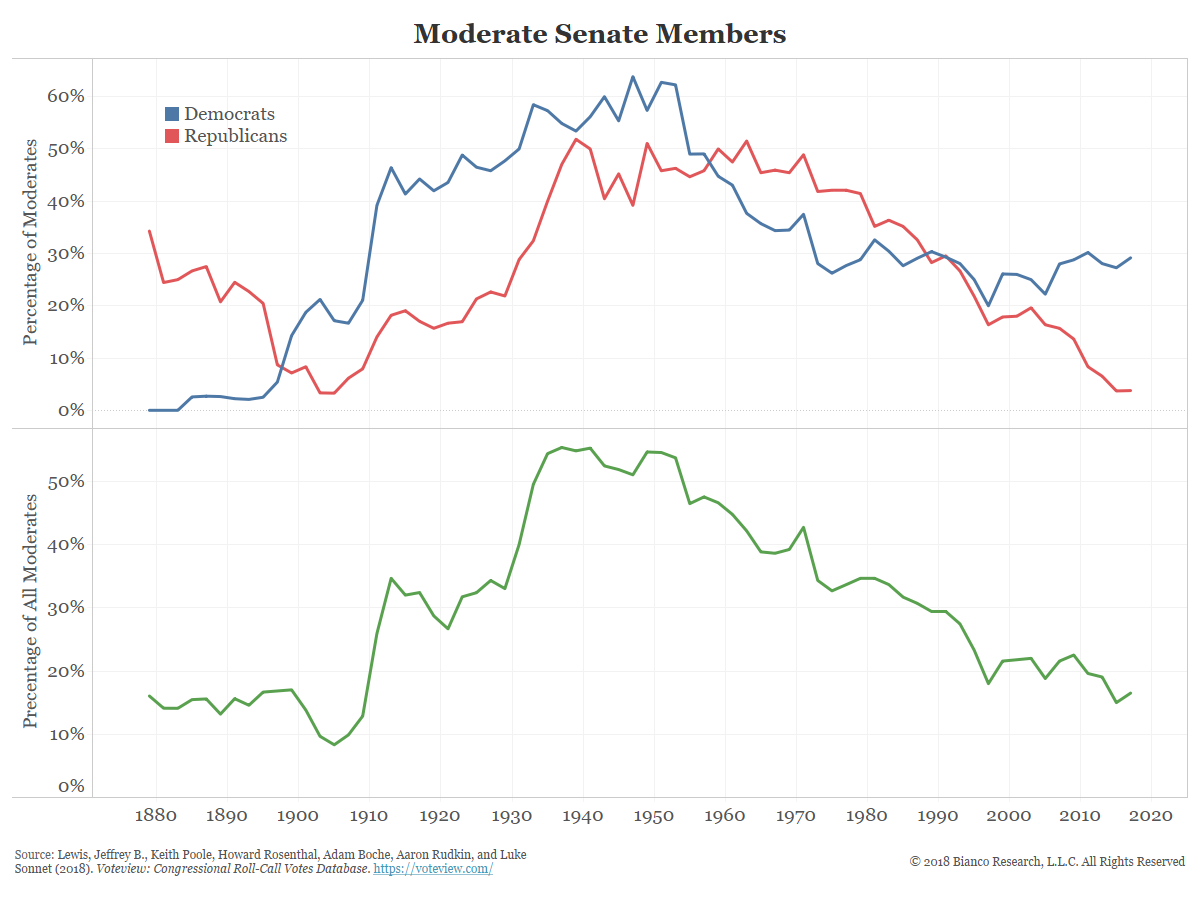

While the chart above shows a divide in the public’s opinion, how polarized are the politicians in Congress?

To measure this we turn to the Vote View project at UCLA. They use a statistical scaling method called NOMINATE (an acronym for Nominal Three-Step Estimation). Details of the methodology can be found here. In 2016, Keith T. Poole, Princeton professor and co-creator of this project, was awarded the Society for Political Methodology’s Career Achievement Award.

Simply, the NOMINATE data measures voting patterns along various dimensions. The first dimension is along party lines. In other words, how often do voting patterns purely fall along party lines?

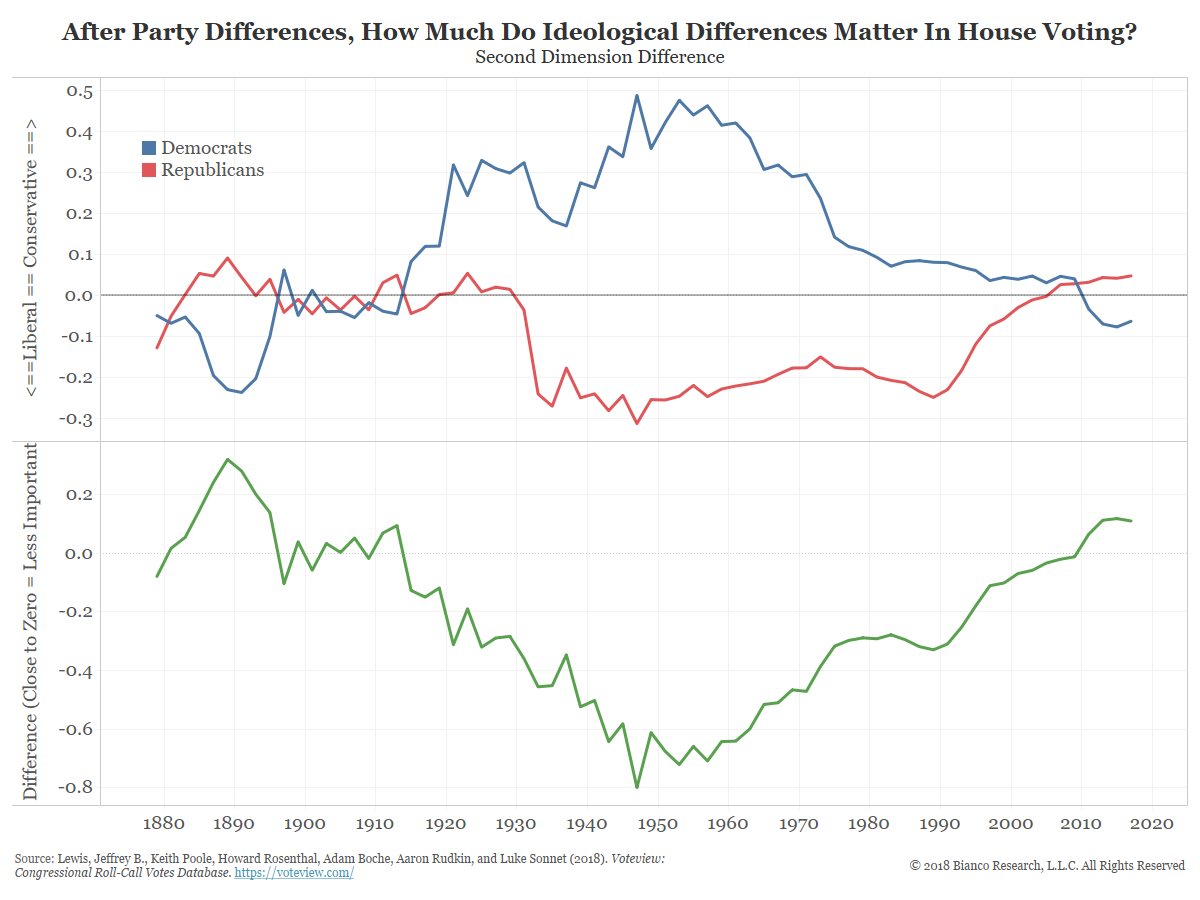

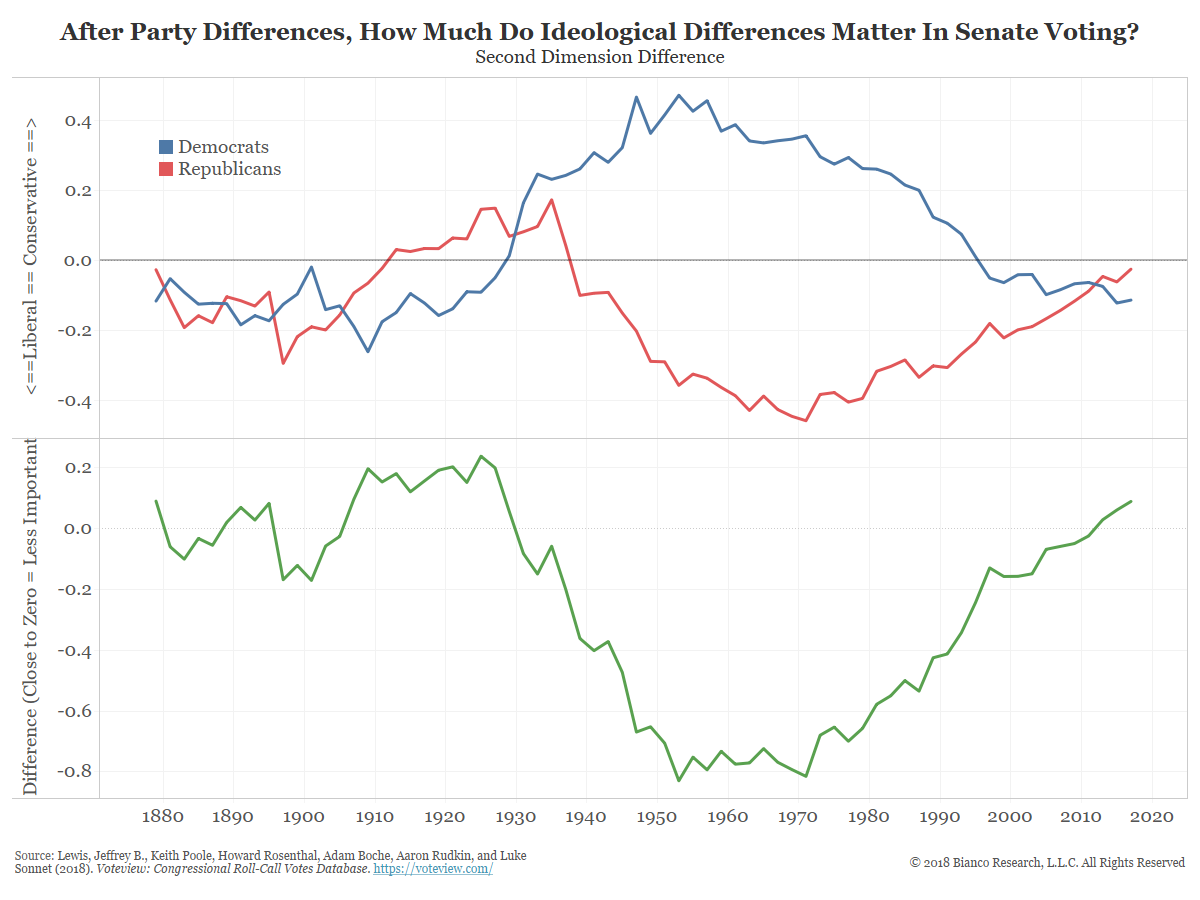

The second dimension is along ideological lines. Or, how often does the specific bill cause voting to diverge from party voting patterns? Remember, all of this is done via statistical modeling, not subjective political scientists making judgments.

To calculate this, Vote View compiled the results of every Congressional vote back to the 1780s, totaling more than 106,000 votes!

All votes are put on a -1 (most liberal/Democrat) to +1 (most conservative/Republican) scale.

Party Lines Votes

The following set of charts show how liberal/conservative each party voted in every Congressional session since 1880. Republicans are shown in red, Democrats in blue, and the difference between them is in green in the bottom panel.

The House vote is the most polarized since the end Civil War, as can be seen in the new high in the green spread.

The interactive chart below offers several parameters that can be changed to zero in on specific periods, starting with Congressional session #1 in 1780.

The white space starting in the late 1990s between Republicans and Democrats points to very little party crossover on votes. The only other time Congress was this polarized was the Civil War when the country split into two.

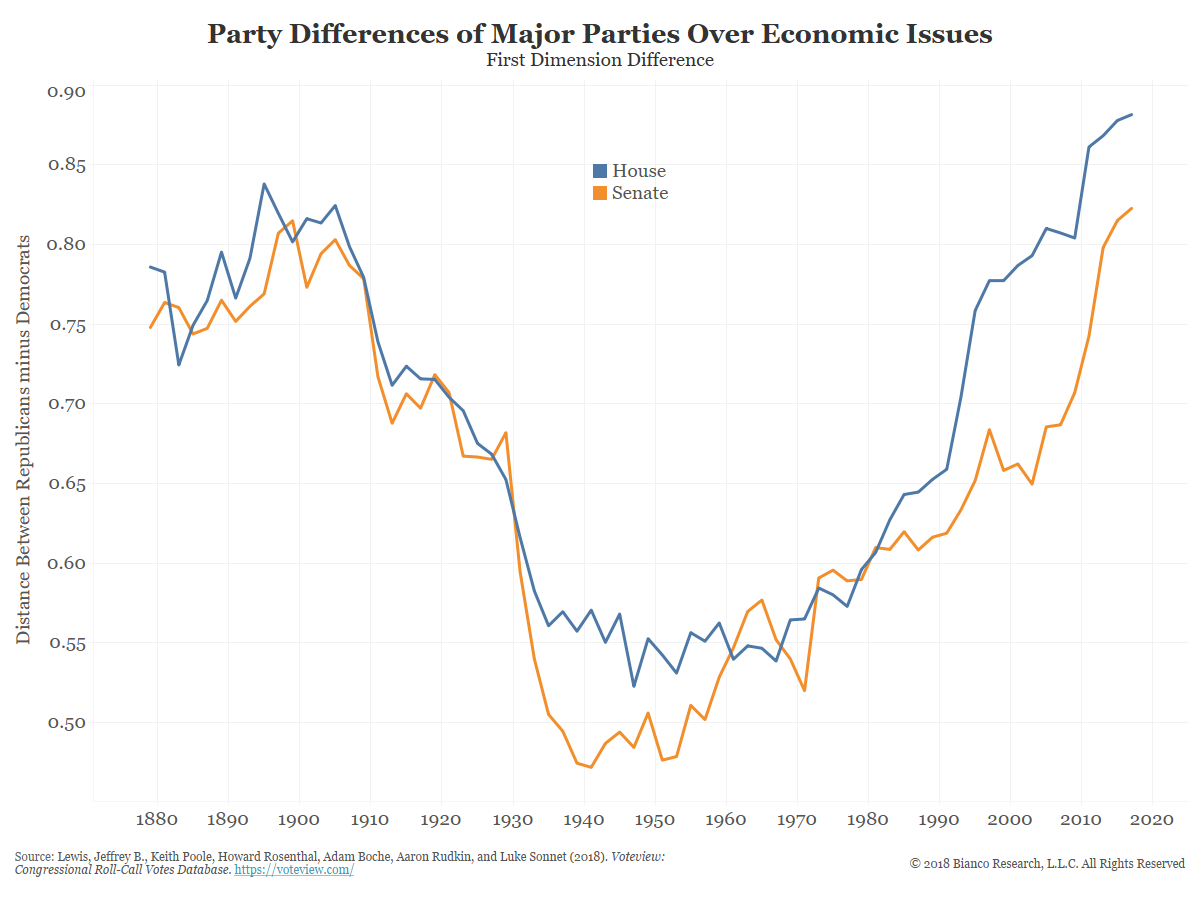

What About Ideology?

The charts above show the most polarized voting patterns in American history. As the Vote View blog noted in 2017:

American politics since November 2000 has resulted in Congressional voting to collapse into a one dimensional near Parliamentary voting structure; that is, the parties are very unified as shown by Party Unity Scores.

The next two charts below focus on the second dimension – how often does a specific bill get politicians to vote based on ideological aspects rather than party affiliation?

In the House, politicians used to vote based on ideological aspects from the 1930s to roughly 2000. Since then, however, the degree to which ideological aspects matter to a vote has collapsed to almost zero. Simply put, political affiliation trumps ideological values.

Conclusion

The 1930s satirist H.L Mencken once quipped:

Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it

U.S. politics is the most polarized it has been since at least the Civil War, and this simply reflects the divergence in opinions among the public.

All indications are the midterm election results will make this even more extreme, not less.